One of the biggest point-shaving scandals in American sports history began with two students playing video games in an apartment at Arizona State University.

On the sticks of this particular Sega Genesis was Stevin ‘Hedake’ Smith, a star point guard with the Sun Devils who had just returned from playing overseas with the US U-21 basketball team. Joining him was Benny Silman, someone he had met on campus as a freshman and had known for years.

On the court, Smith was already getting noticed by NBA scouts for his court vision and record-breaking scoring, and seemed set for a glittering career in the professional ranks.

But soon, he and Silman began gambling on the outcomes of their game of choice. Smith began losing. His friend offered him the chance to clear his small debt by placing bets on a pair of upcoming NFL games. The basketball star lost both of those too.

Weeks of betting with Silman went by before Smith racked up a debt of over $10,000. It was then that Silman – who Smith eventually realized was the ASU campus bookie – approached him with a simple way to clear the debt: fixing basketball games.

In his senior year in 1994, the point guard rigged five games he took part in as part of an operation tied to organized crime. Three years later, Smith and teammate Isaac Burton were arrested, pled guilty to conspiracy charges and served a year in prison.

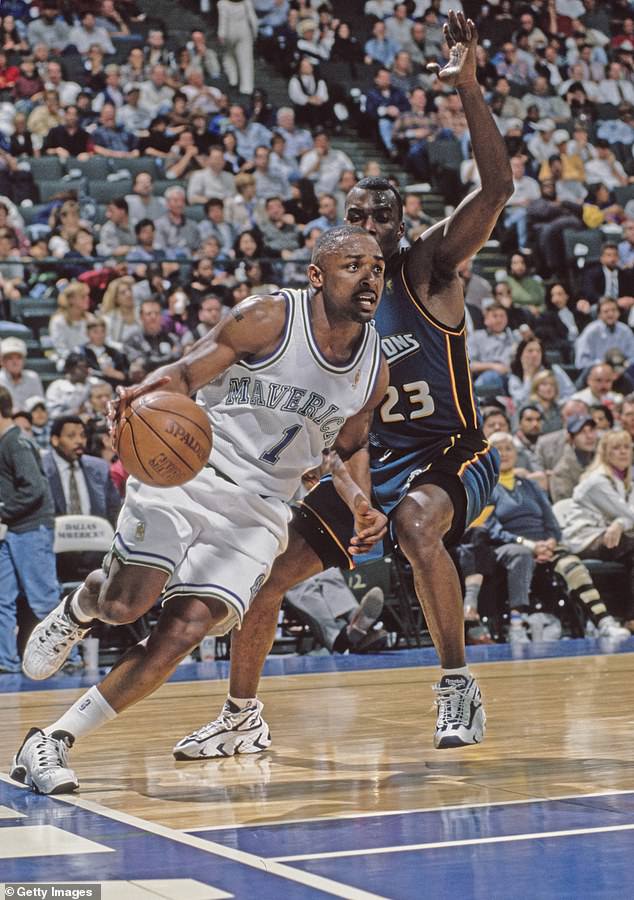

Stevin ‘Hedake’ Smith was at the center of one of the most notorious point shaving scandals in NCAA history

Smith, who once played for the Dallas Mavericks, spent over a year in prison for a match fixing scandal when he was in college that ruined his once promising shot at an NBA career

With college basketball currently embroiled in yet another point shaving scandal, Smith exclusively spoke to the Daily Mail about his story – one of the most powerful cautionary tales in the sport.

Once Silman hooked Smith on the scheme, the star player knew exactly how to operate to ensure the best outcome.

‘As a point guard, I knew who couldn’t shoot. I knew what most players could do,’ he explained. ‘I controlled the tempo, so I would slow it up. When I get to the basket, penetrate, I would kick it to non-shooters.’

Smith admits it’s easier to say these things outside of his speaking engagements ‘because I don’t want to give [athletes] no ideas or nothing.’

But it’s what made his job in fixing so easy: ‘I knew their weaknesses and everything. Because of the style of play and the knowledge that I have, I was able to orchestrate that.’

The first game he fixed against Oregon State University went perfectly. When asked to win by no more than six points, Smith and Arizona State won by exactly that amount – clearing his debt and earning him thousands.

For Smith, who grew up poor in Dallas, the sight of that much money was life-changing.

‘My mama was making $30,000 a year. I had a chance to make $20,000 in 40 minutes. For me, it was a no-brainer,’ he admitted. ‘And plus, I wasn’t educated on it.

‘The education I had in gambling was shooting dice and playing cards because that’s what I grew up doing. That’s what I knew as gambling to be.

‘But the outcome of a game, as they call it, white-collar crime, I didn’t know the meaning of it.’

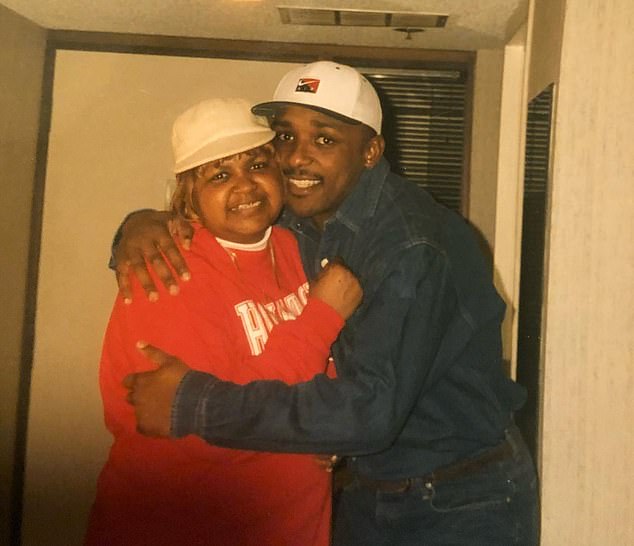

He sent some of the money back home to his mother Eunice, who gave him the nickname ‘Headache’ as a child due to his high energy. She became so proud of him that she put that nickname on her license plate – shortening it to ‘Hedake’.

Of course, he splashed some cash for himself too: ‘I went to the mall, bought all kinds of Jordans and everything. I wasn’t eating in the cafeteria no more. I was eating at everywhere that cost money. I wasn’t even parking in the student parking. I was parking at the meter in the other garage.’

Smith starred at Arizona State when he fixed five games in his senior season. He initially got involved to clear a gambling debt, but ended up raking in thousands of dollars in cash.

Smith racked up his gambling debt with on-campus bookmaker Benny Silman (left, in 2016)

Smith made sure to give back to his mother Eunice, but spent plenty of money on himself

Asked why he kept going, Smith was brutally honest: ‘It was for the love of money.’

He added, ‘You’re talking about when you go to someone from a low-income environment, and you see that cash, and you’re that young, immature, of course you’re going, “Yeah, I’m down.”‘

But there was another reason why Smith stayed involved in the scheme: he wasn’t asked to throw the game away entirely.

‘Here’s the key: We can win. We’re not asking you to lose, but it’s only [win] by so many points,’ Smith explained.

‘And the bookie always picked the game because it had to be a game where we was favorite by double digits. It was never no single-digit game that he tried to manipulate.’

The games were also all at home, with Silman watching on.

As the scheme continued, Smith involved Burton, who didn’t need much convincing: ‘Of course, I’d do it for you,’ Smith recalls his teammate saying.

Burton was in on the scheme, ‘Because of the respect. He knew I had nice things. He wasn’t really eating. Back then, we didn’t have NILs or nothing.’

Eventually, Smith also recruited teammate Isaac Burton (24) to join in on the scheme

Eventually, the scheme fell apart as word got out and betting lines moved aggressively

With his debt erased and some cash in his pocket, Smith could have stopped after fixing games against Oregon State, Oregon and USC. Instead, he got involved on his own – putting a $20,000 wager on himself for a game against UCLA. When that failed, he ended up fixing one more game against Washington.

In the lead up to the Washington game, other bettors got wind of the action and made wagers – violently moving the betting lines and tipping off authorities.

‘It was over because so much money was lost. Benny skipped town, everything went downhill after that,’ Smith said.

Arizona State missed the NCAA Tournament that season and crashed out in the first round of the NIT. Smith was still projected to be a first-round NBA draft pick in a class that included the likes of Glenn Robinson, Jason Kidd and Grant Hill.

But after inviting friends and family over to his house to watch the draft, Smith ended the evening by himself without hearing his name called. It turns out, NBA teams had gotten wind of his point-shaving involvement and steered clear.

After playing in Spain and in the Continental Basketball Association, Smith signed a 10-day contract with the Dallas Mavericks in 1997. He would log eight NBA games across his career before continuing to play abroad on teams in Turkey and France.

While at home with his mother in the summer of 1997, Smith got a knock on his door. The FBI was waiting on the other side.

He was taken to a park and shown pictures of bettors caught up in the scandal, only recognizing two of them. Soon after, he was arrested.

Both Smith and Burton pled guilty to charges of conspiracy and he was sentenced to a year plus one day in prison. Silman was sentenced to under four years in prison for his role.

Smith’s brief NBA career with the Mavericks was cut short after his arrest and prison time

After getting out in 2000, Smith continued playing abroad, heading to France, Israel, Russia and Italy.

Along the way, he began mentoring children in Dallas – using his past discretions as examples of behaviors to avoid.

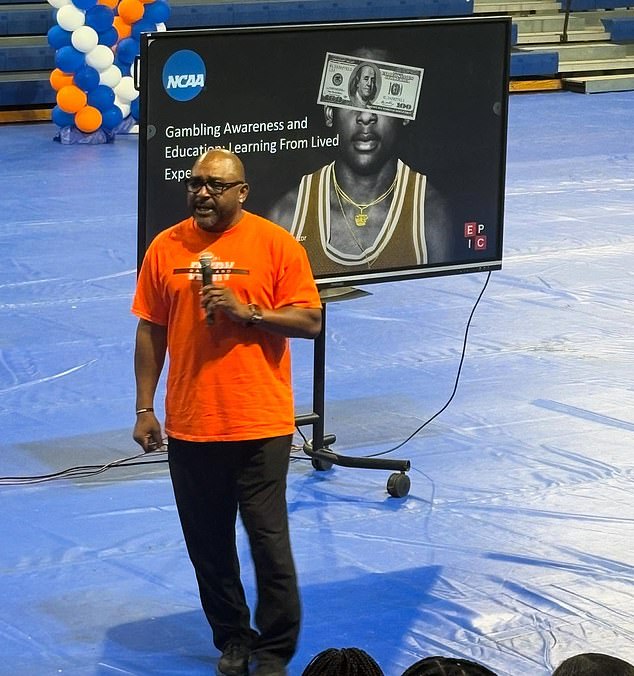

Now, he also works with EPIC, traveling around the country to NCAA institutions to educate athletes on the dangers of gambling and how to avoid it.

Discussions like this help to prevent massive scandals like the one uncovered in mid-January.

The investigation found 17 Division-I schools had combined 39 players participating in a point-shaving scheme across the past two college basketball seasons. Some of those players were on rosters this year.

While Smith doesn’t have any inside knowledge of this scandal, he does have a key insight into why athletes get caught up in gambling. The same could be said for one of his fellow EPIC employees, Dr Brian Selman – a former Alabama football player who won a national title in 2009.

‘The things that made us elite performers in sport, relatively, are also things that can make you a really terrible gambler,’ Dr Selman revealed.

He would continue to play overseas before retiring to work as a mentor and public speaker

‘You’ve thought your entire life that greater levels of effort and work will lead to the outcomes that you want. That’s a hell of a strategy to double down over and over and get buried, just like Hedake did.

‘You think that you understand and know the game at a level differently than most, and therefore that gives you a competitive advantage. That can be very dangerous.’

Smith has another theory, one that passes simple athletic drive and gets at a deeper issue in society.

‘Very seldom do you see a Caucasian involved in this. It’s always going to be Afro-American. Think about it.

‘Now, when you do see a Caucasian involved in this, guess what level it’s at? It ain’t as a player. It’s on a higher level, bigger picture, a referee, coach or something. Because that’s on a bigger stage.’

Point shaving scandals like Smith’s and this most recent one are easy to sweep under the rug or completely miss because of how easy it is to cover up and overlook signs of gambling addiction, Dr Selman explained.

‘If I’m your teammate, and we go to practice every day, and all of a sudden you start noticing that I’m physically sluggish, and you keep walking up to me and you’re like, “Man, you smell like the bar,” or you smell like bourbon, or cigarettes, or whatever else, it’s pretty obvious for you what’s going on that’s affecting my performance,’ he said.

‘I think the nuances of it and the fact that the marketplace has grown so exponentially big and the education and the monitoring lags behind it, that gap is where you see people think they can get away with it.’

Smith, seen speaking to the University of Texas basketball team in February 2026

Another aspect is the level of the schools involved. Taking this most recent scandal as an example, DePaul University is the only basketball team playing in one of the ‘Big Five’ conferences, the Big East. Even then, the Blue Demons have been toward the bottom of the league for the better part of two decades.

So, when players at smaller institutions are shown financial opportunities that only the top athletes may see via NIL deals, Smith believes that’s a way in.

‘That’s part of the manipulation. “Hey, them guys getting millions. Now, you can make money, but just do it this way.”‘

‘For me, greed is what gets everybody caught. There’s no way you can make $2,500 $5,000 easy and stop. This is why I say we need to educate these athletes because everybody ain’t going to make it to the NBA.’

Which is where Smith comes in – traveling the country and telling his story to ‘humanize’ the issue and how it affects individuals, but also those associated with them.

‘If you are a person that has a gambling problem, it affects 6-10 people around you,’ Smith notes. ‘When I say this, I start sweating – because I think back to when I was in this situation. “Damn, I was affecting my mom, my cousins, my team.” People connected to me.

‘The thing is, we’re not educated on that and that’s the deep part of it.’

That education he lacked is now what Smith provides in his nationwide tour, where he does his best to prevent the next generation of athletes from throwing away their potential – and possible future earnings – in the pursuit of some quick cash.